Rediscovered Ithaca film's topic relevant to issues today

By Joe Wilensky

Ithaca Journal Staff

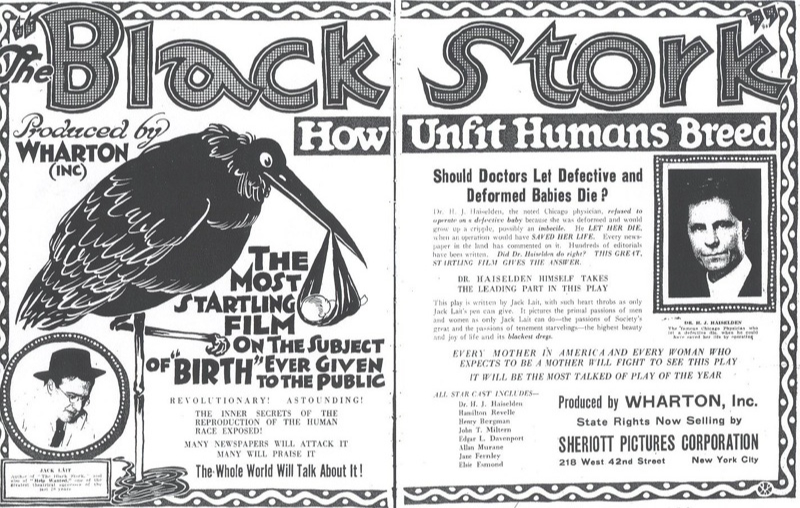

It was called a "eugenic photoplay." Filmed in Ithaca in 1916, with many outdoor scenes at Renwick (now Stewart) Park, the premise of the silent film The Black Stork is: if babies aren't born perfect, do nothing at birth to save their lives --and even help them die.

The film is one of dozens that were shot at Wharton Studios in Ithaca during the silent era, but it is certainly the most controversial, since it dealt with the then-active eugenics movement. For decades, it was thought that there were no surviving copies of the movie, but a local film historian recently located one.

For more than a decade, Terry Harbin, a clerk at the Tompkins County Public LIbrary, has been chronicling Ithaca's brief seven-year starring role in the burgeoning film industry, and has assisted in converting many of them to video with help of the U.S. Library of Congress.

Theodore and Leopold Wharton made dozens of silent films and popular serials, such as The Eagle's Eye, Patria and The Romance of Elaine in Ithaca between 1913 and 1920. Many sets were built right next to the Whartons' studios in Renwick (now Stewart) Park and Cayuga Lake and the many nearby gorges were used for numerous sequences. Ithaca residents appeared as characters and extras in scenes for years.

Harbin knew the Whartons had made The Black Stork with many scenes filmed in Ithaca, but thought no existing copies remained. But he recently discovered a book, The Black Stork: Eugenics and the Death of 'Defective' Babies in American Medicine and Motion Pictures since 1915, written by University of Michigan professor Martin S. Pernick, in 1996.

Pernick, a history professor and the associate director for the university's Program in Society and Medicine, had discovered an aging copy of "The Black Stork" more than 25 years ago.

"The main focus of his book was this movie," Harbin said. Pernick had actually found a rerelease of the movie, a 1927 film, Are You Fit to Marry?, that added a new introduction and conclusions to the 1917 Black Stork.

Based on a real case

Dr. Harry J. Haiselden was a prominant Chicago surgeon who made headlines in the mid-1910's by allowing the deaths of at least half a dozen infants he diagnosed as "defectives." He publicized his efforts to eliminate the "unfit" by displaying the dying babies to reporters, writing about his cause in newspapers and appearing in The Black Stork, which was based on one of his cases.

The movie, originally shot on five reels, chronicles the story of a mother who gives birth to a "defective" baby. In agonizing over whether to ask the doctors to save the infant, she imagines her son growing up as a crippled hunchback, ridiculed and shunned as a child and later vilified by society.

Harbin said Haiselden electrified the country at the time and was as well known for his cause as Dr. Jack Kevorkian was known for doctor-assisted suicide in the 1990's. But Haiselden died just a few years later, effectively ending his personal crusade, although the eugenics movement continued.

The 1927 version introduces The Black Stork as a story a father tells a man who wants to marry his daughter. His aim: The young man has to have a physical examination before marriage to make sure he doesn't carry "tainted blood" -- essentially any disease or undesirable trait -- that would be passed on to future children.

The Black Stork is a forgotten part of medical history, as well as a forgotten part of motion picture history," Pernick said.

Pernick specializes in the role of value issues in medicine and in exploring the issues in medicine and in exploring the links between medicine and mass culture. "There are similarities and differences between "The Black Stork' era and our own, Pernick said Wednesday in a telephone interview. "Certainly, we have much more detailed and accurate technical knowledge about heredity than anyone could have imagined in 1916, and also, partly in response to past abuses of eugenics, we have a much stronger medical and legal emphasis on individual patient rights and informed consent [today].

"On the other hand, there are similarities and continuities as well. Individual choice is not a magic bullet that automatically protects against abuse. In "The Black Stork' era, a lot of the decisions that were made to eliminate 'unfit' infants were made by individual parents, and not by anyone forcing anybody to do anything. Increased technical knowledge can exacerbate probelms, as well as solve them. Both then and now, bothe eras know more abut the science of heredity than any previous generation had. And in both eras, the effort to come up with purely technical, objective definitions of who was 'fit' and who was 'unfit' didn't succeed in keeping out social values --it only succeeded in blinding people to the value judgements they were making.

"The lesson of 'The Black Stork' shouldn't be to feel so superior to [the people then] because their values let them corrupt their science -- are we able to see our own value judgements when we judge somthing as a "birth defect" and decide on a course of treatment?"

"Eugenics ws not simply value-laden genetics," Pernick said. "All genetics, all medicine, is value laden. Eugenics was a movement that was convinced that its values were objective truth. I see some well-meaning similarities in modern efforts to keep genetics purely technical, purely objective, blinding us to the value judgements that we will inevitably be making."

"Even recognizing any human difference as a disease involves a value judgement, in the sense that it's a bad thing to have, that people shouldn't have to suffer with it," he continued. "The 'badness' of disease is not a technical finding from lab results -- it's a value judgement about the evaluation of that difference. We shouldn't expect the most sophisticated DNA technology in the world to define badness for us."

Defining 'eugenics'

The term "eugenics" was coined by Francis Galton, Charles Darwin's cousin. The concept, which began in the 1870's, took "social Darwinism" -- the fittest will naturally survive -- a step further. As Pernick describes in his book: "...eugenics favored active intervention to assist natural selection, to offset medical and charitable activities that had artificially preserved the unfit, and to streamline the slow, wasteful, and cruel aspects of natural competition."

But in the broadest sense, eugenics can be defined as the use of science to improve human heredity, Pernick said. "If you take it at face value, all genetic medicine today could be incorporated into this definition. The controversy is over what counts as an improvement, what methods are scientific --and, who should have the power to answer the other three questions?"

In that sense, the eugenics movement as a concept hasn't ever really ended, he said. While the American Eugenics Society only existed from the early 1920's through the World War II era, "eugenics" as a concept a lot of people profess to believe in, began in the 1870's and has continues to be important today, now more often as a negative label than a positive one, but one that we still fight over what it means." Pernick said.

The most expansive definition of eugenics "could incorporate all of medicine and social reform," he said. "If it were about improving 'heredity,' meaning anything that parents pass on to their children, then eugenics is about being a good parent, making a better future."

"It wasn't just scientists who had the power to shape the meaning of eugenics," he added. " This film really shows how journalists, filmmakers, audiences, censors, the mass public and the mass media, were all battling to control the meaning of that word. The controversy over Dr. Haiselden's actions in not treating impaired newborns. He was criticized more for making The Black Stork than for not treating the infants he allowed to die."

Film's historical role

"The Black Stork" is also important in the history of film, Pernick said. "It's the only surviving example of dozens of silent-era films on eugenics. ...In the period before the Hollywood Code of the 1930's, film dealt with a much broader range of social, moral and political topics than most peope today could imagine. In part, films like The Black Stork helped provoke the rise of a kind of aesthetic censorship that went far beyond just eliminating sexuality from entertainment films, to attempting to eliminate all unpleasant or upsetting themes."

In 1917, the year The Black Stork was released nationally, the Pennsylvania board of censors explicitly censored any film that mentioned eugenics to its list of forbidden topics, Pernick said.

Pennsylvania's code later became a model for a part of the Hollywood Code, that which sought to eliminate "any unpleasant depictions of disease or medical treatments that might upset audiences," Pernick said. The Black Stork was, in some ways, a turning point in the development of this kind of aesthetic censorship that created the Hollywood feel-good film."

After Harbin discovered Pernick's book, he ws able to obtain a copy of the 1927 version of the film on video -- it's currently only available for educational or research purposes. He was also able to find a handful of photos at The History Center in Tompkins County, previously unidentified and unlabeled, and has identified them as stills and publicity shots from the film.